Climate change disrupts the weather patterns of the last 10,000 years, for which we have geological proof. The migratory and birthing cycles of the natural world depend on the established seasonal changes. Plants and animals suffer because of the disruption, as well as from acid rain and a lack of precipitation. Most of nature is not built for heat waves of climate change, especially in our area. The natural world simply cannot adapt quickly enough to match human destruction.

Unfortunately, habitat loss for land-use changes is one of the fastest ways humans affect biodiversity. Close to 95% of the total biomass (living weight) of all land mammals now consists of people and our livestock2. The result is wild habitat destruction: Current extinction rates are 1000 times greater than before the spread of humanity3.

We don’t always know what we are destroying. Of the millions of species of life on Earth, many have not been studied thoroughly. Scientists are only beginning to understand mycorrhizae, for example - the composite structure of fungi and roots that live everywhere in the soil and have for roughly 450 million years4. Abundant life forms such as these have escaped our awareness until now; there are estimates of still millions more we don’t even know of yet.

However, according to the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report from 2022, global species have declined by 69% on average since 1970. Some populations face much higher numbers - up to 94% biodiversity loss in regional Latin American species5.

Pollinator loss is a great example of how climate change will impact ecosystems and, in return, humans. Bees, other insects, and some birds and mammals are all pollinators. They are critical for our world food supply. Pollinators are necessary for plant growth, and plants - aside from providing food - help purify water and protect land from erosion. Without one, the other cannot thrive.

For years, bees have been a poster child for these impacts, and for good reason: bee populations have decreased 40% globally due to pesticides, parasites and disease. Bird populations too are down 60%, and some studies estimate a 70% decline in species overall6.

The effects of climate change aren’t only felt in flying species, either. The world’s aquatic life also faces species death at an inordinate rate. Freshwater organisms have lost 83% of their population since 1970 - the greatest of any group7. Additionally, nearly 50% of marine life has died. The oceans are home to 160 times more life than land8. Coral reefs, called the nurseries of the ocean, are also dying due to ocean acidification from carbon dioxide (CO2) absorption and a rise in water temperature, which the reefs are not prepared to handle.

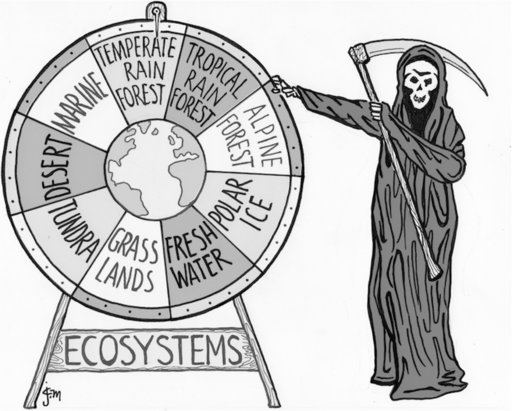

Because all of nature is interconnected, the impacts of climate change affect each organism in different ways and to varying degrees. We are part of it, needing it for our very survival. If we protect nature, allowing regeneration, then all species benefit -the very essence of reciprocity.